In last week’s blog, we revealed what beckoned us to build our fifth and most ambitious Attic Self Storage facility in Beckton. We also held our breaths as we discussed the Sewage-On-Thames and the Great Stink – now let’s find out how the big smelly mess was cleaned up.

YOU’LL NEED A BAZALGETTE TO FIX THAT

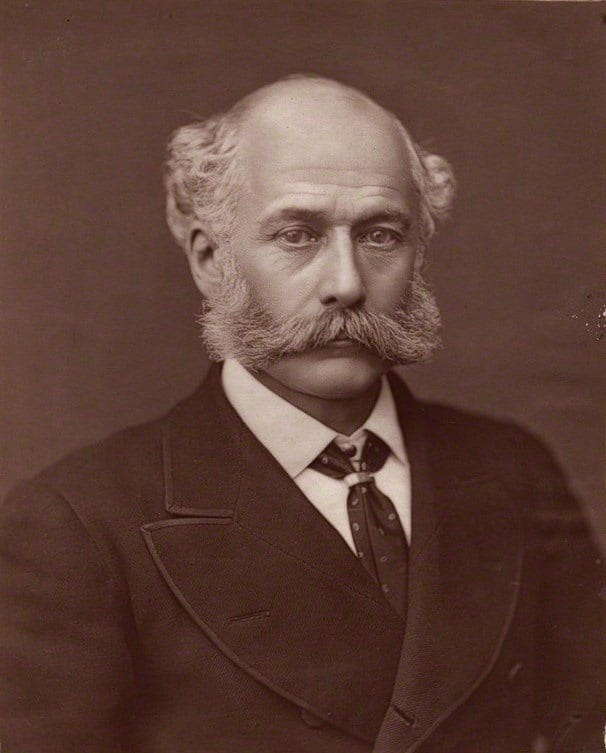

The man put in charge of cleaning up this right royal mess was Joseph Bazalgette – a 19th century English civil engineer with a French Protestant family name.

Backed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, he was appointed chief engineer of London’s Metropolitan Board of Works in 1856.

Two years later, as a result of The Great Stink, parliament finally voted through Mr Bazalgette’s colossally expensive ‘original’ plans, which some suggest were plagiarized from painter John Martin who’d proposed something very similar 25 years earlier.

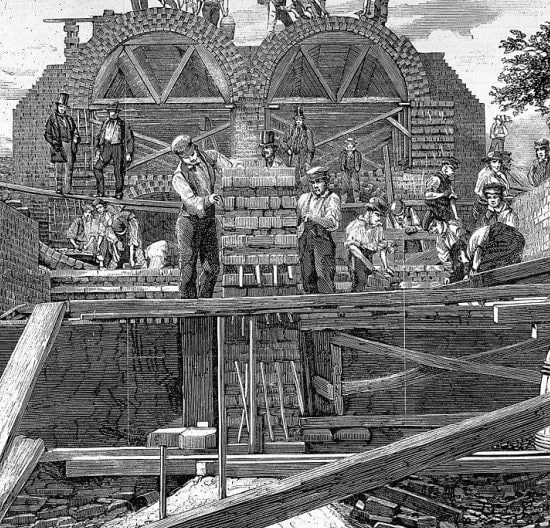

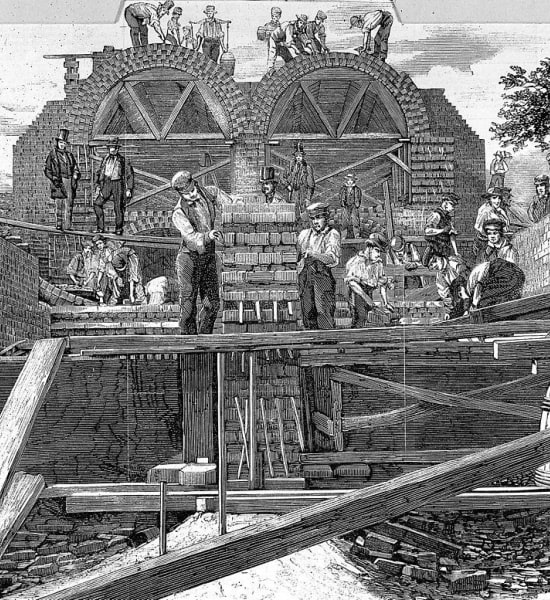

Bazalgette oversaw the construction of 82 miles (132 km) of enclosed underground brick main sewers and 1,100 miles (1,800 km) of street sewers to divert the flow of waste below street level.

The works included building four pumping stations and the Northern and Southern outfall sewers which channeled the horrific toxic soup into huge balancing tanks at Crossness, and yes – Beckton – before being dumped, untreated, straight into the river and from there out to sea.

This revolutionary but somewhat faulty system was inaugurated with much pomp and ceremony by Edward, Prince of Wales in 1865, although it took another 10 years to finish. Over budget and marred by delays.

THERE’S LOADS MORE IN THE PIPELINE

The Treatment Works at Beckton, East London was completed in 1864, at the eastern end of the Northern outfall sewer. It was the first man-made intrusion into the hitherto empty East Ham Levels.

Today, Beckton is still home to Europe’s 7th largest sewage works, treating over 200 million gallons of wastewater a day, and managed by Thames Water.. One of many water supply companies that are once again legally permitted to dump raw sewage back into England’s green and unpleasant water system.

On a brighter note, Beckton sewage works generate more than half the power it needs through its wind turbine and other renewables.

It has recently been expanded to handle the flow from the grand Thames Tideway Tunnel – a 25 km combined sewer running across Inner London to capture, store and convey the raw sewage and rainwater that currently overflows into the estuary.

As a side note, you’ll be pleased to learn that all the units at Attic Self Storage’s new Beckton facility have been designed to exacting health and safety standards. Each one is fresh, clean, airy, and odorless – Attic is pleased to certify itself totally miasma-free.

Right, just when you thought it was safe to tuck into your scrambled eggs.

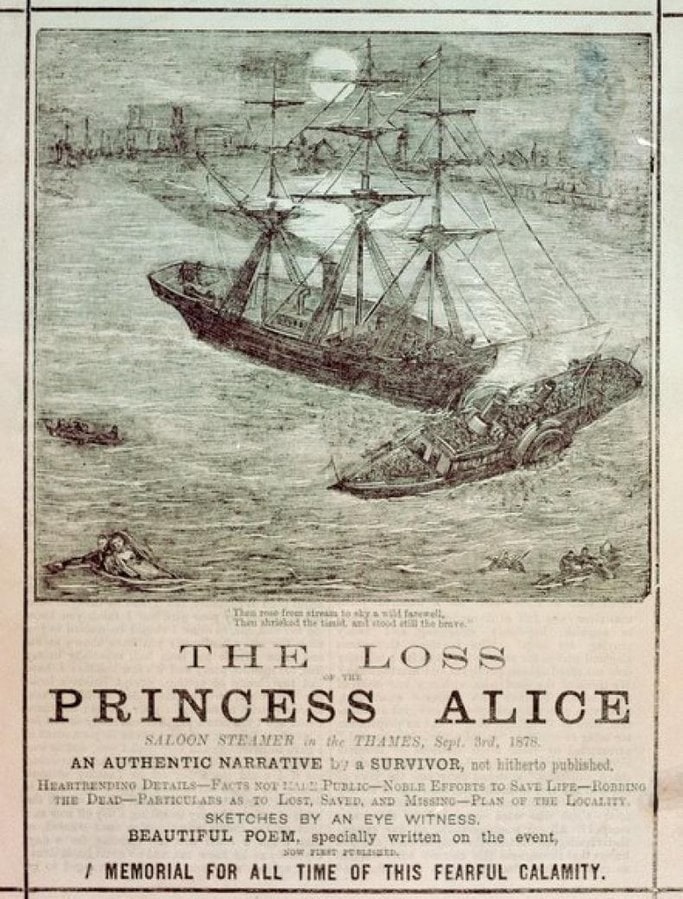

ALICE IN BLUNDERLAND

SS Princess Alice was a passenger paddle steamer that sank on the 3rd of September 1878 after a collision with a coal ship. Nearly 700 people died – the greatest loss of life of any British inland waterway shipping accident.

About 130 people were rescued from the disaster, but many of the survivors later died from ingesting the foul, polluted water. Unfortunately, the accident happened at a point just downstream from the two main – freshly built – sewer outfalls. The twice-daily release of 75 million imperial gallons of raw sewage into the Thames at high tide had occurred one hour before the collision.

In a letter to The Times shortly after the event, a chemist described the outflow in horrific detail:

“Two continuous columns of decomposed fermenting sewage, hissing like soda-water with baneful gases, so black that the water is stained for miles and discharging a corrupt charnel-house odour, that will be remembered by all as being particularly depressing and sickening.”

The water was also tainted by the untreated output from Beckton Gas Works and several local factories. Just to add a further little soupçon of foulness to this chemical cocktail, a fire in Thames Street earlier that day had coated the surface of the river with a thick layer of oil and petrol.

Those poor, poor people. What an awful way to go.

LET THERE BE LIGHT

OK, you can breathe again now.

In 1868 the Gas, Light and Coke Company established its London base on the north bank of the river at Gallions Reach and the whole 550-acre site was named, as we’ve said already, after the governor of the company, Simon Adams Beck.

At its peak, Beckton supplied gas to over four million Londoners, as well as manufacturing creosote, fertilisers, inks, dyes, mothballs, sulphuric acid and other delightful treats – all by-products of the process of turning coal into coke and producing gas.

When Britain started the grand conversion to ‘natural’ North Sea gas in 1966, the gas works days were numbered. At its peak Beckton had employed 4,500 people, but by the late 1970s only 100 employees remained. The site eventually closed in 1976, and is now pretty much derelict, although some pipes and ducts still seem to be hanging around.

SKIING IN THE BECKTON ALPS

A range of mountains rose in the east, their foothills, slopes and peaks layered and overlaid in fading shades of black and grey. Created, not by the natural thrust and collision of the continental shelves, but dumped in an ever spreading spoil-heap from the backside of the coke business that was fueling London’s success at the time.

Most of the waste came from Beckton gasworks but it also included debris from the basement of the new British Library, and local legend tells of a railway locomotive buried at the base. Along with a few forgotten criminals probably.

“Beckton Alps”, as the locals nicknamed them with typical East End irony, originally ran from the Northern Outfall Sewer to Winsor Terrace, where the Premier Inn stands today. But this wasn’t somewhere that tourists flocked in the winter with their mirror shades, salopettes and garish UV lipscreen.

At one point in history, funnily enough, they did try to exploit the Alpine angle and turn the mountains of waste into a miniature Méribel. During 1989, the toxic spoil heaps were landscaped and turned into a 25 metre high artificial ski slope, with a viewing platform at the summit and a Swiss-style bar at the base.

No one less than Her Royal Highness, Diana, Princess of Wales, presided over the opening ceremony.

A few heavyweights from the world of skiing threw their weight behind the venture too:

But like so many other visionary building projects, it failed to capture the paying public’s imagination and finally closed in 2001. Perhaps it was the lack of real snow, or sunshine, or of any real interest from the locals, that led to the demise of the project. The site is now pretty much derelict. Or, in modern parlance, rewilded, which means that nature has been left to take over the toxic spoil heap, and nobody has to water the plants.

TO BE CONTINUED…

Next week we will learn about the housing crisis, a great British hotel, and how we plan to create a brighter future for Beckton!