Unpacking The History From Our Newest East End Attic

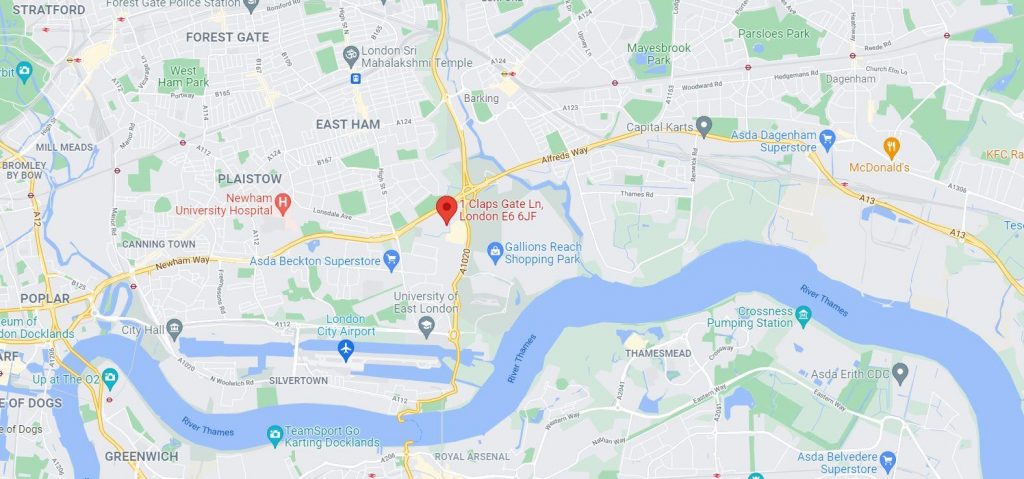

In these following weeks, we’re digging up the history of Beckton, East London – as well as a large plot of land at the back of the local Sainsbury’s car park – where we’re constructing the fifth, and most ambitious, Attic Self Storage facility in our rapidly expanding portfolio.

WHY BECKTON BECKONED

Historically, this part of London has never had the Monopoly board cachet of swanky areas like Mayfair or Park Lane. But it’s chock-a-block with space-age potential if you squint your eyes and use your imagination a little bit.

Attic chose to ‘build back better’ in Beckton because it’s perfectly placed just off the A13, at the eastern gateway into the capital, close to City Airport, well served by bus, tube, and DLR services, and just a London brick’s throw from the Royal Docks and the River Thames.

Attic’s little pocket of land – E6 6JF – is actually the dream location for us, because we can custom build something new, green and sustainable, rather than having to convert an existing building at vast expense.

But what was here before our ‘considerate construction’ started to take shape? (Apart from that 90-year old willow tree that we’re protecting while creating our glass and steel cathedral to St. Orage).

PREPOSTEROUS PREHISTORIC PREAMBLE

This whole area of land was left to its own devices for thousands of years.

A swathe of Jurassic mud-flats that time forgot. A boggy mosquito-infested marshland where dragonflies hovered above snapping ichthyosaurs, saber-toothed butterflies fluttered by, and pterodactyls terrorised ptarmigans. Probably.

Once our early ancestors crawled out of the sea, shed their fins and gills, and quickly invented tools, weapons and the concept of royal hegemony, this would’ve been the kind of place where folkloric mediaeval princesses wandered about in the mist, kissing frogs, hoping to discover a prince – preferably not one called Andrew.

Before being swallowed up by the London Borough of Newham, Beckton was historically part of Essex. But, so far at least, we haven’t unearthed any evidence of prehistoric tanning shops, fossilised stiletto heels, or early earthenware pampas grass pots.

BECK IN THE DAY

It seems humans stayed pretty much clear of this floodplain until the industrial revolution of the 1800s when the dark satanic mills and factory furnaces of ‘The Smoke’ demanded feeding, fueling, and powering.

That’s where Simon Adams Beck fits in. The man who put the ‘Beck’ into Beckton. Mr. Beck was the governor of the Gas Light and Coke Company and oversaw the construction of the sprawling Beckton Gas Works complex that began here in November 1868.

But before we get to the gas, let’s deal with the sh…

WELCOME TO SEWAGE–ON–THAMES

If you’re reading this over your breakfast, we suggest you skip the next few sordid chapters of the capital’s history and head straight for the fresh air of the Beckton Alps.

Still here?

OK, let’s take a deep breath and carry on…

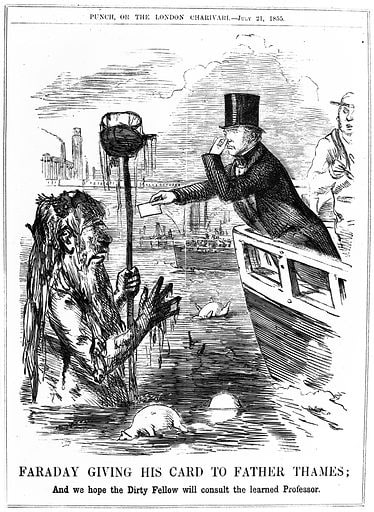

As London’s population grew and grew, so did the amount of wee and poo, and it all ended up in the river. The Thames became a testament to this basic by-product of humanity – a slithering brown stream of raw effluent, spewing east out of the city. No fish, no eels, no cockney crayfish givin’ it all that round these ends, guv’nor.

When the novel Little Dorrit was published as a serial between 1855 and 1857, Charles Dickens described the capital’s main waterway as “a deadly sewer… in the place of a fine, fresh river”.

FOLLOW THE SCIENCE?

A cholera epidemic in 1848–49 killed 14,137 Londoners. Another in 1853 killed a further 10,738 people. The experts of the day didn’t make the connection between using the Thames as a toilet and the spread of the disease.

‘Follow the science’ from the time and you’d believe that cholera was caused by foul air – or a miasma as it was known.

The fog, smog and cloying clouds of chimney smoke that often hung over the city, no doubt helped to propagate this misconception.

THE GREAT STINK

In June of 1858, temperature in the shadiest parts of the capital (there were plenty of those around Beckton) averaged between 34-36 degrees centigrade, rising to 48℃ if you were foolish enough to venture out in the midday sun, with or without your mad dog.

Thanks to the warm dry weather, the level of the river Thames dropped considerably and raw effluent was left clinging to the banks where it congealed in the sun.

How’s your stomach?

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert (the actual people, not pubs) attempted to take a summer pleasure cruise but were driven back by the awful smell. Her Majesty wasn’t amused. That did it. When royal nostrils are offended, something has to be done.

As ever, the London press obediently weighed in, dubbing the event “The Great Stink”, and demanded that the Thames be cleaned up immediately, if not sooner.

Old Father Thames’s reputation was properly dragged through the mud:

“Gentility of speech is at an end – it stinks, and whoso once inhales the stink can never forget it and count himself lucky if he lives to remember it”, reported one journalist. The London Standard went so far as to suggest that the capital’s main artery was “A pestiferous and typhus breeding abomination”.

Nice.

TO BE CONTINUED…

Next week we will learn about the man put in charge of cleaning up this right royal mess, The loss of the Princess Alice, and the Beckton Alps! Stay tuned!